The

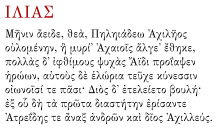

Odyssey (

Greek:

Ὀδύσσεια,

Odýsseia) is one of two major ancient

Greek epic poems attributed to

Homer. It is, in part, a sequel to the

Iliad, the other work traditionally ascribed to Homer. The poem is fundamental to the modern

Western canon. Indeed it is the second—the

Iliad being the first—extant work of Western literature. It was probably composed near the end of the eighth century BC, somewhere in

Ionia, the Greek-speaking coastal region of what is now

Turkey.

[1]

The poem mainly centers on the Greek hero

Odysseus (or Ulysses, as he was known in

Roman myths) and his long journey home following the fall of

Troy. It takes Odysseus ten years to reach

Ithaca after the ten-year

Trojan War.

[2] In his absence, it is assumed he has died, and his wife

Penelope and son

Telemachus must deal with a group of unruly suitors, the Mnesteres (Greek: Μνηστῆρες) or

Proci, competing for Penelope's hand in marriage.

It continues to be read in the

Homeric Greek and translated into modern languages around the world. The original poem was composed in an oral tradition by an

aoidos (epic poet/singer), perhaps a

rhapsode (professional performer), and was intended more to be sung than read.

[1] The details of the ancient oral performance, and the story's conversion to a written work inspire continual debate among scholars. The

Odyssey was written in a regionless poetic dialect of Greek and comprises 12,110 lines of

dactylic hexameter.

[3] Among the most impressive elements of the text are its

non-linear plot, and that events seem to depend as much on the choices made by women and

serfs as on the actions of fighting men. In the

English language as well as many others, the word

odyssey has come to refer to an epic voyage.

Synopsis

Telemachus, Odysseus's son, is only a month old when Odysseus sets out for Troy to fight a war he doesn't want any part of, and which he has been told will last a long time.

[4] At the point where the

Odyssey begins, ten years after the end of the ten-year

Trojan War, Telemachus is twenty and is sharing his absent father’s house on the island of Ithaca with his mother

Penelope and a crowd of 108 boisterous young men, "the Suitors", whose aim is to persuade Penelope that her husband is dead and that she should marry one of them.

Odysseus’s protectress, the goddess

Athena, discusses his fate with

Zeus, king of the gods, at a moment when Odysseus's enemy, the god of the sea

Poseidon, is absent from

Mount Olympus. Then, disguised as a Taphian chieftain named

Mentes, she visits Telemachus to urge him to search for news of his father. He offers her hospitality; they observe the Suitors dining rowdily, and the bard

Phemius performing a narrative poem for them. Penelope objects to Phemius's theme, the "Return from Troy"

[5] because it reminds her of her missing husband, but Telemachus rebuts her objections.

That night, Athena disguised as Telemachus finds a ship and crew for the true Telemachus. The next morning, Telemachus calls an assembly of citizens of Ithaca to discuss what should be done to the suitors. Accompanied by Athena (now disguised as his friend

Mentor), he departs for the Greek mainland and the household of

Nestor, most venerable of the Greek warriors at Troy, now at home in

Pylos. From there, Telemachus rides overland, accompanied by Nestor's son, to

Sparta, where he finds

Menelaus and

Helen, now reconciled. He is told that they returned to

Sparta after a long voyage by way of

Egypt; there, on the island of

Pharos, Menelaus encountered

Eidothea, the daughter of the old sea-god

Proteus, who told him that Odysseus was a captive of the nymph

Calypso. Incidentally, Telemachus learns the fate of Menelaus’ brother

Agamemnon, king of

Mycenae and leader of the Greeks at Troy, murdered on his return home by his wife

Clytemnestra and her lover

Aegisthus.

Then the story of Odysseus is told. He has spent seven years in captivity on Calypso's island. She is persuaded to release him by the messenger god

Hermes, who has been sent by Zeus in response to Athena's plea. Odysseus builds a raft and is given clothing, food and drink by Calypso. The raft is wrecked by Poseidon, but Odysseus swims ashore on the island of

Scherie, where, naked and exhausted, he hides in a pile of leaves and falls asleep. The next morning, awakened by the laughter of girls, he sees the young

Nausicaa, who has gone to the seashore with her maids to wash clothes. He appeals to her for help. She encourages him to seek the hospitality of her parents,

Arete and

Alcinous. Odysseus is welcomed and is not at first asked for his name. He remains for several days, takes part in a

pentathlon, and hears the blind singer

Demodocus perform two narrative poems. The first is an otherwise obscure incident of the Trojan War, the "Quarrel of Odysseus and

Achilles"; the second is the amusing tale of a love affair between two Olympian gods,

Ares and

Aphrodite. Finally, Odysseus asks Demodocus to return to the Trojan War theme and tell of the

Trojan Horse, a stratagem in which Odysseus had played a leading role. Unable to hide his emotion as he relives this episode, Odysseus at last reveals his identity. He then begins to tell the amazing story of his return from Troy.

After a piratical raid on

Ismaros in the land of the

Cicones, he and his twelve ships were driven off course by storms. They visited the lethargic

Lotus-Eaters and were captured by the

Cyclops Polyphemus, only escaping by blinding him with a wooden stake. While they were escaping, however, Odysseus foolishly told Polyphemus his identity, and Polyphemus told his father, Poseidon, who had blinded him. They stayed with

Aeolus, the master of the winds; he gave Odysseus a leather bag containing all the winds, except the west wind, a gift that should have ensured a safe return home. However, the sailors foolishly opened the bag while Odysseus slept, thinking that it contained gold. All of the winds flew out and the resulting storm drove the ships back the way they had come, just as Ithaca came into sight.

After pleading in vain with Aeolus to help them again, they re-embarked and encountered the cannibalistic

Laestrygones. Odysseus’s ship was the only one to escape. He sailed on and visited the witch-goddess

Circe. She turned half of his men into swine after feeding them cheese and wine. Hermes warned Odysseus about Circe and gave Odysseus a drug called

moly, a resistance to Circe’s magic. Circe, being attracted to Odysseus' resistance, fell in love with him and released his men. Odysseus and his crew remained with her on the island for one year, while they feasted and drank. Finally, Odysseus' men convinced Odysseus that it was time to leave for Ithaca. Guided by Circe's instructions, Odysseus and his crew crossed the ocean and reached a harbor at the western edge of the world, where Odysseus sacrificed to the dead and summoned the spirit of the old prophet

Tiresias to advise him. Next Odysseus met the spirit of his own mother, who had died of grief during his long absence; from her, he learned for the first time news of his own household, threatened by the greed of the suitors. Here, too, he met the spirits of famous women and famous men; notably he encountered the spirit of Agamemnon, of whose murder he now learned, who also warned him about the dangers of women (for Odysseus' encounter with the dead, see also

Nekuia).

Returning to Circe’s island, they were advised by her on the remaining stages of the journey. They skirted the land of the

Sirens, passed between the six-headed monster

Scylla and the whirlpool

Charybdis, and landed on the island of

Thrinacia. There, Odysseus’ men ignored the warnings of Tiresias and Circe, and hunted down the sacred cattle of the sun god

Helios. This sacrilege was punished by a shipwreck in which all but Odysseus drowned. He was washed ashore on the island of Calypso, where she compelled him to remain as her lover for seven years before he escaped.

Having listened with rapt attention to his story, the

Phaeacians, who are skilled mariners, agree to help Odysseus get home. They deliver him at night, while he is fast asleep, to a hidden harbor on Ithaca. He finds his way to the hut of one of his own former slaves, the swineherd

Eumaeus. Athena disguises Odysseus as a wandering beggar in order to learn how things stand in his household. After dinner, he tells the farm laborers a fictitious tale of himself: he was born in

Crete, had led a party of Cretans to fight alongside other Greeks in the Trojan War, and had then spent seven years at the court of the king of Egypt; finally he had been shipwrecked in

Thesprotia and crossed from there to Ithaca.

Meanwhile, Telemachus sails home from Sparta, evading an ambush set by the suitors. He disembarks on the coast of Ithaca and makes for Eumaeus’s hut. Father and son meet; Odysseus identifies himself to Telemachus (but still not to Eumaeus) and they determine that the suitors must be killed. Telemachus gets home first. Accompanied by Eumaeus, Odysseus now returns to his own house, still pretending to be a beggar. He experiences the suitors’ rowdy behavior and plans their death. He meets Penelope and tests her intentions with an invented story of his birth in Crete, where, he says, he once met Odysseus. Closely questioned, he adds that he had recently been in Thesprotia and had learned something there of Odysseus’s recent wanderings.

Odysseus’s identity is discovered by the housekeeper,

Eurycleia, as she is washing his feet and discovers an old scar Odysseus received during a boar hunt. He received the scar when he was hunting with the sons of Autolycus. They had been told to go boar hunting so that they could prepare a meal with the meat. The three climbed Mount Parnassus and eventually came across a boar in a large and deep meadow. Because of the meadow's depth, the three hunters were ambushed by the seemingly invisible boar and when Odysseus first saw the animal, he rushed at it but the animal was too fast and slashed him in the right thigh. Despite being gored by the boar, Odysseus still hit his mark and stabbed the boar through the shoulder. Odysseus' bleeding was staunched by a spell that was chanted by the sons of Autolycus and he received great glory and treasure for his bravery

[6]. Having seen this scar, Eurycleia tries to tell Penelope about Odysseus' true identity, but Athena makes sure that Penelope cannot hear Eurykleia. Meanwhile Odysseus swears her to secrecy, threatening to kill her if she tells anyone. The next day, at Athena’s prompting, Penelope maneuvers the suitors into competing for her hand with an archery competition using Odysseus' bow. The man who can string the bow and shoot it through a dozen axe heads would win. Odysseus takes part in the competition himself; he alone is strong enough to string the bow and shoot it through the dozen axe heads, making him the winner. He turns his arrows on the suitors and with the help of Athena, Telemachus, Eumaeus and Philoteus the cowherd, all the suitors are killed. Odysseus and Telemachus hang twelve of their household maids, who betrayed Penelope and/or had sex with the suitors; they mutilate and kill the goatherd

Melanthius, who had mocked and abused Odysseus. Now at last, Odysseus identifies himself to Penelope. She is hesitant, but accepts him when he mentions that their bed was made from an olive tree still rooted to the ground. Many modern and ancient scholars take this to be the original ending of the Odyssey, and the rest is an interpolation.

The next day he and Telemachus visit the country farm of his old father

Laertes, who likewise accepts his identity only when Odysseus correctly describes the orchard that Laertes once gave him.

The citizens of Ithaca have followed Odysseus on the road, planning to avenge the killing of the Suitors, their sons. Their leader points out that Odysseus has now caused the deaths of two generations of the men of Ithaca—his sailors, not one of whom survived, and the suitors, whom he has now executed. The goddess Athena intervenes and persuades both sides to give up the vendetta. After this, Ithaca is at peace once more, concluding the

Odyssey. Yet Odysseus' journey is not complete, as he is still fated to wander. The gods have decreed that Odysseus cannot rest until he wanders so far inland that he meets a people who have never heard of an oar or of the sea. He then must build a shrine and sacrifice before he can return home for good.

[7]